- Home

- M. H. Herlong

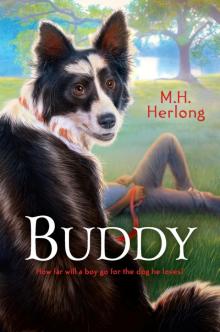

Buddy Page 8

Buddy Read online

Page 8

“You were just watching and making up a song about what you were seeing, weren’t you?”

Tanya presses her fingers against her eyes.

“And when it didn’t work out, you blamed Buddy?” Daddy says.

Tanya almost nods.

“That ain’t right,” Daddy says.

“Don’t hit her with the stick,” I say. “She’s too little.”

Daddy looks at me a second, then he says, “I guess I’ll go take that board off the door. Ain’t no use in keeping him penned up. We’ll get the rats tomorrow.”

When he leaves out, I sit down beside Tanya on the kitchen floor.

“I’m glad you told the truth,” I say.

We’re listening to Daddy’s hammer prying off that old board and Buddy barking and barking. Tanya’s sniffing and rubbing her nose like she wants to rub it off.

“You want to see my new bike?” I say.

“Can I ride it?”

“You ain’t big enough,” I say.

She follows me out to the front yard, and I pick up the bike where I dropped it. We’re standing there looking at the red bike when Buddy comes limping around from the back. He comes up and sniffs me and pokes his nose in my hand. Then he goes to sniff Tanya.

“I’m sorry, Buddy,” she says. “I know you’re Li’l T’s dog, but I love you, too.”

He bends down and licks those red shoes on her feet, and all a sudden I’m wondering if Buddy loves her back.

17

I wish it wouldn’t happen but it always does. No matter what, along comes August and off we go to school. I don’t see J-Boy anywhere, so I don’t have to worry about him anymore. Now it’s that boy Rusty sitting next to me instead. I tell him I have a dog, and he says he wishes he had one, and I say why don’t you come by my house someday and see mine, and he says okay. I ask him does he like to draw, and he shrugs his shoulders and says maybe.

We’ve been in school only a week when Daddy comes home from work Saturday evening and Granpa T meets him on the steps.

“Did you hear about this storm?” Granpa T says.

“What kind of storm?” Daddy says.

“It’s a hurricane,” Granpa T says. “They call it Katrina. They say it’s a bad one.”

“They’re all bad,” Daddy says.

“The mayor says we ought to leave,” Granpa T says.

“He always says that,” Daddy says. “Remember last time?”

Last time we didn’t have Baby Terrell yet. He was still just a big old bump in Mama’s stomach. Last time when the mayor said, “Get out of town,” we all piled in the car and drove to Mississippi where Granpa T’s people stay. Aunt Joyce, Granpa T’s niece, let us stay in the spare room in her house. Mama and Daddy, me and Tanya, and Granpa T—all in the same room. We were all sound asleep when Mama started moaning in the middle of the night. Daddy said, “Oh, Lord,” and pretty soon the whole house was awake except Granpa T and he was doing his going away trick that ain’t really sleeping.

By morning we had a baby brother and the storm was somewhere in north Alabama. Daddy said we got to go home because he’s got to work and I got to go to school. So we left Mama and Tanya and the baby in Mississippi with Aunt Joyce and got on the road with everybody in the whole city of New Orleans trying to get back. The sky was bluer than I’d ever seen and the sun was so hot I thought it was going to make the paint curl up off the roof of the car.

“I remember last time,” Granpa T says, “and all I can say is, thank the Lord she ain’t pregnant again.”

“I mean the way everybody got all excited,” Daddy says, “and then nothing happened. Those storms don’t hit New Orleans. They always turn at the end.”

“Don’t let the devil hear you say that,” Granpa T says, and he goes inside.

Sunday morning we go to church and the preacher looks at me and says, “I heard about what that dog did.”

I say, “He’s a good dog, Brother James. He takes care of things. He’s walking real good now. He even climbs up a few steps. I’m going to make him a pirate leg and he’ll do even better.”

“You’re the instrument of God,” Brother James says. “God was waiting for your car so that dog could have a happy life.”

“With only three legs?” I say.

“There’s always a price,” Brother James says, and shakes his head. “Happiness always comes with a price.”

When he calls us to prayer, he talks about Buddy. He talks about how everybody came together and saved God’s creature and how helping each other is what God meant us to do.

And then he starts praying louder. He raises up his voice and he says, “A storm is coming, Lord. A storm is coming.”

At first I think he’s talking about evil as usual, but this time he’s talking about rain and wind.

“The mayor came on the TV this morning,” Brother James prays. “He came on the TV and he said, ‘You got to leave.’ He said it’s mandatory. And, Lord, what does mandatory mean? It means you got to. Lord, we got to leave our homes.

“Lord, there’s some of us who have a way. We’ve got cars or we’ve got people who’ve got cars. Lord, give us the strength to gather our families and put them in the cars and take them to safety.

“But, Lord, there’s some of us who don’t have a way. Some of us are too old and some of us are too young and some of us are too poor. Lord, help us to reach out to our brothers and sisters who don’t have a way. Help us to put them in our cars with us. Help us to take them to the Superdome if they need a ride. Help us, Lord, to help each other—just like we helped old Buddy—so we can gather together again next Sunday and raise our voices in praise and joy just like we’re doing today. Hallelujah!”

And the choir starts singing, and Mama casts her eye on Daddy and Daddy looks back at her and raises up his eyebrows, and I know we’re leaving again.

Mama starts packing the minute we get home. She starts with Baby Terrell’s stuff. She pulls out all his diapers and bottles and toys and stroller and port-a-crib, and then Daddy says, “We can’t take all that, woman.” And Mama makes a face like she’s sucking a lemon but she puts back the toys and the stroller and the port-a-crib.

“Who’re we going to take with us?” I say to her. “Like Brother James says?”

Mama stops stuffing a bag and looks at me. “You haven’t got the sense you were born with, boy. Where are we going to put somebody else? Tie them on the roof?” She shakes her head and snatches up Baby Terrell right before he pulls over the lamp. “Go get a suitcase,” she says. “Pack two nights of clothes. Help Tanya pack, too.”

Daddy’s in the kitchen filling up a cooler and Granpa T’s shifting around in his room putting things in a paper sack.

“Maybe we ought to take Mrs. Washington to the Superdome,” I say to him.

“We’d have to drag her out,” Granpa T says. “And anyway, how’s she going to make do with all those strangers and she’s half blind?”

He sets his sack on the table and I look inside. There’s a box of pictures, his Bible, his pills, and two pair of undershorts.

“You’re packing light,” I say.

“We ain’t going to be gone long.”

Tanya’s sitting on the sofa with her doll, about to cry.

“Do what your mama told you to do,” Granpa T says. “Go help your sister pack.”

So I drag Tanya upstairs and make her pick out some clothes. We’re fighting about whether she can pack her ballerina skirt and those red shoes when I hear Daddy calling me.

“Li’l T,” he’s yelling. “Go get Buddy and bring him inside.”

I go running down the stairs. “Why inside?” I say.

“Can’t leave him outside,” Daddy says.

“Leave?” I say.

“We can’t take Budd

y with us,” Daddy says. “There ain’t room in the car.”

All a sudden, I can’t move. I’m standing there like a statue. My fingertips are throbbing and my feet feel like rocks.

“Then I won’t go,” I say.

Daddy stops still and stares at me.

“I’ll stay here with Buddy. I’ll look after the house. Y’all won’t be gone long. Maybe I’ll go stay with Mrs. Washington.”

“I said bring Buddy inside.” Daddy’s looking at me like he’s one inch away from getting that stick up by the shed. “Now,” he says, and turns around and walks off.

I go outside and Buddy’s laying on his blanket. He lifts up his nose when he sees me, and his tail goes thump. I sit down and rest my elbows on my knees. Then I bend down my head and hold it in my two hands.

I ain’t touching Buddy or even looking at him. But I can feel him. It’s like the whole shed is filled up with him being there. He moves his feet and his claws scratch a little on the floor. His tail thumps against the wall. I hear him breathing—not panting but not real quiet either. I know the tip of his tongue is hanging out the side of his mouth. I know his whole body is moving just the slightest bit with each breath. Then I hear his teeth click together when he closes his mouth and the rustle of the blanket as he lays his head down. I know he’s looking at me with his big, soft eyes just like he always does.

I can’t leave Buddy.

I can’t not leave Buddy.

I lift up my head and see his eyes turned up to look at me. He waits a second then he gets up and limps over to where I’m sitting. He pokes his nose at my hand where it’s holding up my head. He licks my ear.

I know they’re all running around like crazy inside. I know I could just walk out the gate and Buddy would follow me and they wouldn’t ever see. I could go wherever I wanted. We could find a shed somewhere and hide. I’d take his blanket and at night we’d sleep on it together. When I was sure everybody was gone, we’d sneak back. His food and his bowls would be waiting. I’d break in the house and make soup. Once the storm passed, I’d check on Mrs. Washington and make sure she was okay. I’d bring her some of the soup. Buddy would lay on her front porch and we’d sit in her swing and she’d give me a cold drink and I’d read her letters to her and maybe I’d cut her grass for free. When I came back home, I’d go up on the roof and fix the hole where a pecan branch broke off in the storm.

Now Buddy’s licking my cheek like it’s a Popsicle. I take his face in my hands and he licks my whole face.

When they got home, the house would be fixed and Mrs. Washington would be safe and they’d say—

All a sudden Granpa T shows up at the door. “You coming, son?” he says.

“I can’t leave Buddy,” I say, and a little hiccup comes out.

Granpa T sits down beside me. “Why do you love that ugly, old dog so much?”

“I just do.”

“I loved my chicken.” Granpa T’s rubbing my back. “Can you imagine that? Loving a chicken?”

I don’t say nothing.

Granpa T stands up. “You ain’t got no choice, son,” he says. “I’ll carry the dog food.”

He grabs up the bag and heads toward the house. I don’t move. He turns around. “We’re all waiting,” he says, and goes on inside.

I stand up and lead Buddy out of the shed. He’s following me, but his tail ain’t wagging.

“Two days,” I’m telling him. “It’s only two days.”

He stops still at the bottom of the steps.

“You can do it,” I say. “You’re strong enough.”

He hops up the steps one at a time. I hold the door open for him. It’s the first time he’s ever been inside. He bends down and starts sniffing at the rug like he ain’t sure this is where he’s supposed to be.

“I don’t like a dog in my house,” Mama says.

“It ain’t your house,” Granpa T says.

“We’re putting him in the big bathroom upstairs,” Daddy says. “We’ll shut him up.”

It’s hard for Buddy to make it up the stairs. Finally, Daddy reaches down and picks him up. “He’s a lot heavier,” Daddy says. “You’re feeding him too much.”

We’re all standing in the bathroom. Buddy’s walking around, sniffing at the corners and poking his nose at the trash can. Granpa T’s running a bathtub full of water. Daddy’s setting up the food bag in the corner and cutting a hole in the bottom so Buddy can eat straight out the bag.

“Where is he going to pee, Daddy?” I say. “Where is he going to do his business?”

“He’ll figure it out,” Daddy says.

Then Buddy starts kind of running around the bathroom in little circles. He’s making whimpery sounds. His tail’s going down between his hind legs. He knows we’re leaving him. He knows what it feels like.

Granpa T turns off the water and Buddy runs over and licks out a little. He’s got enough water to last forever it looks like. He runs over and takes a bite of his food. He comes over and pokes his nose at my hand. His big old brown eyes are looking up at me like he’s wondering if this is for true, like he can’t believe I’d do this to him.

I start toward the door and he’s right beside me. He’s glued up so close I’m almost tripping on him.

“Make him stay,” Daddy says.

I walk to the back of the bathroom and Buddy walks with me.

“Sit, Buddy,” I say, and he sits.

“Stay,” I say, and start backing up toward the door. All a sudden, Daddy grabs my arm and snatches me out the room. Daddy slams the door and we hear Buddy running across the tile. Then we hear him scratching on the door.

“You’re going to have to paint that door when we get back,” Daddy says.

Then Buddy starts to howl. I ain’t never heard that sound before.

“Arrroooo!” Buddy’s crying. “Arrrooo!”

I put my hand on the door and feel it shaking.

“Buddy,” I say, but he just keeps on, wailing and moaning like he ain’t never heard me. Like he ain’t never even known me.

I’m standing there and something big’s trying to go down my throat. I’m feeling my eyes get stingy, and Buddy keeps on howling.

“Two days?” I say to Daddy.

“Two days,” Daddy says.

18

It usually takes an hour and a half to get to Aunt Joyce’s place in Mississippi. This time it takes eight. We’re sitting on the superhighway with everybody and his brother. The cars are backed up along the road as far as you can see, all shining in the hot sun.

When we’re on the bridge crossing Lake Pontchartrain, some cars start driving down the shoulder lane, and Daddy starts cussing.

Mama says, “T Junior, that doesn’t help,” and he shuts up.

It takes us four hours just to get from our house to the other side of that bridge. Once we get across the lake, I see a man get out of the passenger door of a car and walk along the side of the road for a while. He bends down, touches his toes a few times, and does some jumping jacks. Then he turns around and goes back to his car. Traffic is moving that slow.

Baby Terrell starts up fussing and Granpa T’s got his head tilted back as usual. Tanya’s singing to herself in the backseat. After a while, Mama starts up some hymns. I wish I had my Game Boy back.

Eight hours is a long time to sit in a car that ain’t hardly moving.

We make Aunt Joyce’s house long after dark. She’s got a whole plate of fried chicken waiting and a big old pot of gumbo. We eat and we talk. I tell Aunt Joyce all about Buddy. She says she had a dog once. She named him Spot because he had a white circle around one eye. He had four legs but lost part of his ear in a fight. Aunt Joyce can’t remember what became of Spot. She says she’d have to ask her mama and her mama’s passed.

Daddy and Gran

pa T sit out on the front porch and drink their beer. They don’t have any neighbors to talk to because we’re so far out in the country. There ain’t no other houses. There ain’t no cars. There ain’t no lights.

Tanya’s running around in the dark trying to catch fireflies while Aunt Joyce looks for a jar. Mama’s sitting on the swing holding Baby Terrell and humming.

I walk out into the open yard where Aunt Joyce has a little garden growing tomatoes. At home you have to lift the tomatoes up to your nose and give them a good sniff if you want to smell them. Here they soak up the sun all day and then sit there in the dark, sending off their tomato smell to everybody in the yard. I get myself a good noseful and then walk farther out under the trees.

Aunt Joyce must have fifty trees in her yard. They’re tall, tall pine trees. I got to bend my head way back to see the needles all at the top. The wind is moving them just the tiniest bit and they’re making a quiet whush-whushing sound. I can see lots of stars through the trees, but I can see the clouds are starting to blow in, too.

When I get back to the porch, Daddy and Granpa T are looking up. They’re feeling the air.

“It’s coming,” Granpa T says.

“I’ll be glad when it’s gone,” Mama says. “I already want to lie down in my own bed.”

I hear her voice in the dark and I think how quiet it is at home right now with everybody gone.

How quiet and dark.

I’m wondering what Buddy is thinking. I’m wondering if he’s scared.

I wrinkle up my forehead and I squinch my eyes shut and I send him a message. Two days, Buddy, I think. Just wait. Two days.

When I wake up Monday morning, I’m covered in sweat.

We’re all sleeping in the same room again. Mama and Daddy are on the bed. Granpa T is on a sofa pushed against the wall. Baby Terrell’s in a crib borrowed from the people down the road. Me and Tanya are rolled up in blankets on the floor.

The ceiling fan ain’t moving and there ain’t no air coming out the vents. The alarm clock is dead.

And the storm is on us.

I’m laying there, sweating and listening to the wind.

Buddy

Buddy The Great Wide Sea

The Great Wide Sea