- Home

- M. H. Herlong

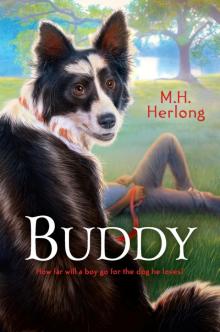

Buddy

Buddy Read online

BUDDY

M. H. Herlong

Viking

An Imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Young Readers Group, 345 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd.)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in the United States of America by Viking,a division of Penguin Young Readers Group, 2012

Copyright © M. H. Herlong, 2012

All rights reserved

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Herlong, M.H.

Buddy / by M. H. Herlong.

p. cm.

Summary: Twelve-year-old Li’l T and his family face great losses caused by Hurricane Katrina, including leaving Buddy, their very special, three-legged dog, behind when they must evacuate.

ISBN 978-1-101-59179-6

[1. Family life—Louisiana—Fiction. 2. Dogs—Fiction. 3. Hurricane Katrina, 2005—Fiction.

4. African Americans—Fiction. 5. Lost and found possessions—Fiction. 6. New Orleans (La.)—Fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.H431267Bud 2012 [Fic]—dc23

2011042854

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

To New Orleans

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Acknowledgments

1

We found Buddy in the middle of St. Roch Avenue at 8:45 on a Sunday morning. That’s the way Granpa T would start this story. “It was early April,” he’d say. “The spring of 2005.”

“Is that so?” somebody else would say.

“It’s a fact,” Granpa T would say, and then he’d nod his head. “I’m going to tell you a story about a dog—a three-legged dog—and a little black boy with no more sense than God gave a grasshopper.”

But Granpa T ain’t telling this story. I’m telling it. My name is Tyrone Elijah Roberts, just like my daddy and Granpa T before him. Everybody calls Daddy “T Junior.” Everybody calls me “Li’l T.”

So this story starts up in the car. We’re on our way to church. It’s hot in the car and we’re crowded. Daddy’s driving and Mama’s sitting in the front seat fanning herself. I’m squeezed in between them and looking at my Game Boy.

I’m about to make it to the next level.

My little sister’s in the back playing the fool with the baby. She’s shaking these big old plastic keys in front of his face and saying, “Grab them. Come on, Baby Terrell. You can do it.”

And Granpa T’s sitting beside the baby seat, leaning back with his mouth open like he’s sleeping but he ain’t sleeping. He’s just gone someplace he goes when he don’t like where he is.

“We need a bigger car, T Junior,” Mama says.

Daddy don’t say nothing.

“Li’l T’s almost thirteen years old. Pretty soon, his feet are going to be sticking out the front window.”

Daddy still don’t say nothing.

“And when Tanya and Terrell both get bigger, it’s going to be way too crowded in this old car.”

“I already said,” Daddy starts up, “we’ll go looking when I get that increase at work. It don’t help to bring it up now.”

Mama casts her eye at Daddy. Then she sighs. “It’s just so hot,” she says. “And it’s only April.”

Daddy nods, and I miss my shot, and it’s Game Over.

We’re riding by the Tomato Man. It’s too early for good tomatoes, but he’s out there selling other stuff just like he does every Sunday morning.

“What’s he got for sale today?” Mama says.

Daddy leans forward a little bit and says, “Sign says collard greens.”

“I don’t want any collard greens,” Mama says.

And then all a sudden Daddy slams on the brakes, and Mama screams, and I’m bending forward toward the dashboard. Mama’s arm slams into my chest, and those plastic keys come flying over the seat and smack the back of my head, and the baby starts crying, and Granpa T sits up straight and says something I can’t write down in this story.

Then the whole world’s still.

We’re sitting in the hot car and the baby’s crying and Mama finally says, “What was that, T Junior?”

And Daddy says, “I think I hit a dog.”

Daddy climbs out of the car first. He opens the door and it creaks like it’s going to fall off but it don’t. He looks up toward the front of the car.

“Oh, Lord,” he says, and I’m crawling out his door while Mama’s grabbing at my leg saying, “Wait,” but one thing I ain’t doing is waiting.

It’s a black dog. A black dog with long, straight fur. He’s laying flat on the street. His tail is stretched out behind him, and he’s still as a stone.

I kneel down in the street right beside him.

“Be careful,” Daddy says, but he don’t stop me.

“Hey, boy,” I say. I reach out my hand toward the dog real slow and touch his head just a little bit. “Easy, now. Easy,” I say.

The dog twitches. And then all a sudden he lifts up his head and looks straight at me.

“He’s alive,” Daddy shouts, and everybody starts piling out the car to come see.

That dog don’t take his eyes off me. He’s looking at me like he’s wondering who I am, and I’m looking right back. His eyes are soft and big and dark, dark brown, with black going all around t

he rims. He’s got a sprinkling of white fur across his forehead and down the top of his nose, sort of in the shape of a heart.

Everybody’s crowding around, but me and that dog are still looking at each other. He’s got a long, thin scar over one of his eyes. The fur around the scar goes every which way, making him look like he’s got a buck moth caterpillar stuck on his forehead. Under his chin and down his throat, the fur is mostly white. One front paw is supposed to be white, too, but it’s so dirty it looks almost brown.

“He sure is dirty,” Mama says. She’s standing there with her hands on her hips and Tanya’s hanging on her like she might fly away.

Granpa T bends down and looks at the dog and says, “His hind leg’s broke.”

“How do you know that?” Daddy says.

“I use my eyes,” Granpa T says, and points.

And sure enough, anybody can see. The top back leg is kind of covering it up, but once you look, you can see the other back leg is bent the wrong way and there’s something white sticking out through the fur. That dog’s leg ain’t just broke. It’s broke bad.

I’m rubbing the dog’s head now. He’s started panting like nobody’s business laying there on the hard street in the hot sun where the shadow from the oak trees ain’t even close to him.

I can feel the hard bone under his soft fur and the way his skin moves a little when I push my hand over the round top of his head. His eyes stretch open and I curl my fingers into the thick fur on his neck.

I bend down and touch the top of the dog’s head with my nose. He smells like dog sweat and old, wet leaves and dry dust all at the same time.

“Be careful, Li’l T,” Mama says.

“Ain’t nothing to worry about,” Granpa T says. “That’s one gentle dog.”

“You can’t tell that,” Daddy says. “He’s still half knocked out.”

Granpa T just shrugs his shoulders.

“What’s your name?” I whisper to the dog.

He sticks up his tongue and licks my chin. I must taste good because he does it twice. Then he shifts a little and his broke leg moves and he yelps and starts to wiggle like he wants to get up.

“Easy, boy,” I say again. “Easy.”

And he settles right down and lays still.

“What are we going to do, Daddy?” I say.

Daddy’s standing there wiping his face with a tissue. Granpa T’s leaning on the side of the car with his arms crossed over his chest.

Mama looks over at the Tomato Man down the road. “Who’s dog is this?” she yells.

Tomato Man’s standing up under his umbrella. He’s looking at us like we’re a movie show. “Ain’t nobody’s,” he hollers back. “Just a street dog.”

“But who feeds him?” Mama yells.

Tomato Man shrugs up his shoulders.

Mama looks down at the dog. “Doesn’t look like anybody feeds him,” she says.

The baby’s crying in the car. Tanya’s twisting her feet in her sandal shoes and wrinkling up Mama’s dress in her hand.

Mama looks at her watch and says, “We’re going to be late for church.”

“He needs a doctor,” Granpa T says.

“We can’t pay a doctor for no dog,” Daddy says.

“But somebody’s got to help him,” Granpa T says.

“Well, we can’t take him with us,” Mama says. “There’s not enough room in the car.”

“We can’t just leave him here neither,” Daddy says.

I’m still kneeling down by the dog. Now he’s resting his head in the palm of my hand, and I’m thinking that my hand is going to smell just like dog.

Just like this dog.

I look up at all those people fussing and I don’t even think about it. All a sudden, I just blurt it out.

“There’ll be plenty enough room,” I say, “if I walk.”

Every one of them stops talking. They all look down and stare at me.

“Put the dog in the back,” I say. “Tanya can take my seat. Somebody at church will know what to do.”

“You’re going to walk to church?” Daddy says.

“He’s not old enough to do that,” Mama says. “This neighborhood—”

“How old are you, boy?” Granpa T says.

“Thirteen next October,” I say.

“I was picking cotton when I was your age,” Granpa T says. He turns to Mama. “I think he can walk five blocks to church. T Junior, put that dog in the car. Standing in this heat ain’t good for my heart.”

When Granpa T says what to do, everybody does it. Mama’s mouth is all screwed up like she’s sucking a lemon, but she don’t say nothing. She buckles Tanya into the front seat and sticks a pacifier in the baby’s mouth so he stops crying.

“Okay, dog,” Daddy says. “I’m going to pick you up and you ain’t going to bite me. We got a deal?”

That dog’s looking at Daddy like he ain’t too sure about this deal.

Daddy squats down and slowly starts to work his arms up under the dog. Granpa T’s helping with the broke leg. The dog twists his head back and forth like he’s trying to look at both of them at the same time. When Daddy lifts him up off the ground, the dog makes a noise like a squeaky toy and then a yelpy sound.

Daddy makes a sound, too, like umph. “He’s boney,” Daddy says, “but he’s heavy enough.”

That dog is whimpering and wiggling like he wants to get away but then Daddy hustles him into the car. The dog takes up all of Tanya’s seat and more, his front feet passing up under the baby seat and his head almost laying in the baby’s lap.

That dog is looking at Baby Terrell but I can’t stop looking at the dog. At first I think his big old eyes are sad and scared because he’s hurt and maybe because he’s hungry. Next I think they’re glad and happy because he’s out of the sun and maybe because he thinks we’re going to feed him. Then he settles his head down and turns his eyes on Mama.

“You watch that dog with my baby, Granpa T,” Mama says. “If he takes even a little nip I’ll throw him out on the street, broke leg and all.”

“He ain’t going to bite Baby Terrell,” I say. “Just look at his eyes.”

Mama gives me a look. “You don’t know anything about that dog,” she says.

“I know that much,” I say.

“Hmph,” Mama says.

Then they’re all in the car and the doors slam shut. Daddy leans out the window. “Keep on walking down this street, son, until you get to St. Claude. Turn left and go on until you see the church. We’ll be inside looking for you.”

I nod. They drive off.

“What are you going to call that dog?” Tomato Man hollers.

“What makes you think I’m going to call him anything?”

Tomato Man laughs and picks up his newspaper. “I know what I know,” is all he says.

2

I started up wanting a dog the day after I was born. At least, that’s what I always tell people. We were living in a double, and my best friend Jamilla and her aunt were living on the other side. For extra money, Mama was making pralines to sell out of the house and watching Jamilla while Jamilla’s aunt was at work. We played on the front porch every day, and I remember every single dog that ever walked by. And there were a lot.

When I was about five or six, a boy down the street named Melvin had a yellow dog that chased a ball. Every day when Jamilla and me got home from school, we watched him walk out with that dog and head to the park. We asked if we could come but he said we were too little. I told Jamilla I wanted a dog just like that. She drew me one on a piece of paper and said, “Here.” Mama stuck it up on my wall and said, “That dog almost looks alive.” I was thinking it was a good picture but it wasn’t that good.

When I was seven years old, I told my daddy I wante

d a dog.

Mama was walking round with a great big stomach, and Daddy said, “We can’t have a dog. We’re going to have a baby.”

I said, “I want a dog, not a baby.”

Daddy said, “You don’t get to choose.”

When I was nine years old, I told my daddy I still wanted a dog, and he said, “We got a toddler baby now. We ain’t got room for a dog.”

When I was ten years old, we moved down the street to live with Granpa T. He said he had a big old empty house and couldn’t work anymore because of his heart trouble, and what were we doing paying rent anyway. Mama had started cooking up lunches to sell, too, so she could use a bigger kitchen. And to tell the truth, Granpa T wasn’t as strong as he ought to be. Jamilla’s drawing got all ripped up when we took it off the wall. She said she would do another one, but I said, “Don’t worry about it. We got a yard now—even though there ain’t hardly no grass.”

So I told my daddy we had enough room now and I still wanted a dog. But he said times were hard and he didn’t have the money to feed a dog.

When Mama’s stomach got big again, I knew there wasn’t no point saying I wanted a dog. We were going to have another baby, and there wasn’t no more money than there was before.

And since Christmas, there ain’t even been as much. Jamilla and her aunt just up and moved. One day when the aunt came by after work to get Jamilla, Mama started up showing off the little plastic bags she had just bought to put her pralines in. Each bag was just big enough for one praline and each one said mama’s pralines in this pinky-red color Mama took about two hours to pick out. She had just bought boxes and boxes of them plus two rolls of ribbon to tie them shut. The aunt was standing there nodding and saying how nice that was going to look. Then all a sudden she stopped nodding and she said, “I need to tell y’all something. We’re moving to Chicago. I got a better job. It’ll be a better school. We’re leaving this weekend.”

We were just standing there staring at her and then she said, “Y’all have been good to Jamilla for ten years, and you’re like family. But we have to go.” Just before Jamilla walked out the door, she turned around and waved. “I’ll write you a letter, Li’l T,” she said, “and then you can write me back.” And that’s the last time I ever talked to her.

Buddy

Buddy The Great Wide Sea

The Great Wide Sea