- Home

- M. H. Herlong

Buddy Page 5

Buddy Read online

Page 5

We’re sitting down to eat dinner when Buddy starts up again. We all rush out the back door and there’s Buddy, barking at the squirrels. He ain’t giving them no polite “ruff, ruff” neither. He sounds like if they get close enough to him he’s going to rip their throats out. They’re chucking and chucking and he’s barking and barking.

We sit back down and Buddy keeps on barking.

“He’s keeping those squirrels off that bird,” Granpa T says.

“Hmph,” Daddy says. “Dogs don’t do that.”

Granpa T looks over at me, and we smile.

9

Next morning Buddy starts up again. Mama says it’s going to drive her up a wall. Daddy says the neighbors are going to start complaining. Granpa T says he’s going to have to shoot either the squirrels or the dog if he’s ever going to take a nap again. Tanya looks like she’s going to start crying and Granpa T says he’s just teasing, and can’t she tell when he’s teasing and when he ain’t.

In the end, Mama don’t climb the wall, the neighbors don’t complain, and Granpa T’s gun stays put. By the time school lets out for the summer, Buddy’s got all the squirrels scared off and I feel like I’m finally out of prison. No more bus to ride. No more teachers going on and on. No more homework. Mama says for the first week I’m on vacation but after that she’s not making any promises.

That first morning I wake up when I please, take care of Buddy, and wander on back into the house where it’s cool. After a while I flip on the TV and there’s Scooby Doo, driving a car or something, and I think, I wonder what Buddy would say to that! Tanya’s sitting there with me. When the commercials come on, she says she wants a doll in a wedding dress for Christmas. Mama says don’t start talking to her about Christmas and when are we going to get up and make our beds and don’t we have anything to do but watch cartoons.

I look outside and there’s Buddy, laying in his cool place in the shade keeping an eye on the yard. I go and sit with him.

“You think it’s this hot in Chicago?” I ask him. I hold the ball in my hand and toss it up and down but Buddy don’t hardly look at it.

“Do you suppose school’s out up there, too?” I put the ball down in front of his nose and he pokes it once or twice but he’s too lazy to move more than that.

“Do you think they swim in that big old lake in the summertime?”

He swishes his tail around in the dust but he don’t move anything else.

“Why do you think Jamilla ain’t never answered my letter?”

Buddy looks at me with his caterpillar eyebrow raised up like he wishes he knew.

“I’m going to write her again,” I say.

Buddy flips his tail to say he thinks that’s a good idea.

“I’m going to tell her how good you’re doing.”

Buddy lays his head down and closes his eyes. I guess he’s had enough of talking.

I just sit there watching him and letting my hand smooth the top of his head over and over. I’m thinking it will be an easy letter to write because there ain’t no doubt about it. Buddy’s doing better. He’s getting around good when he stays inside the yard. His ribs ain’t showing near as bad. His bandage is off, and if you look at him right, you forget there are only three legs.

But all that getting well is hungry work. Buddy’s eating more and more, and my Game Boy money is almost gone. Something’s got to happen, but I don’t know what. I don’t have anything else to sell and I ain’t old enough to get a job. I need another plan.

“What am I going to do, Buddy?” I say, but he don’t say nothing. He’s so asleep his tail don’t even twitch. I lean back against the bark of the tree. I look up. Somewhere behind the leaves is the big old sky.

“You got any ideas?” I say, but the sky don’t answer.

I ask Granpa T if he’ll pay me to mow the lawn and he looks at me and says, “That ain’t even funny. Go on, boy, and find yourself something to do.”

I ask Mama if she’ll pay me to bag up pralines. She says I’ve lost my mind and leave her alone while she’s cooking.

I know better than to say anything to Daddy. That’s just asking for trouble.

I sit down by Baby Terrell. I lean up close and say, “Gootchie, gootchie, goo,” and he whops me with his toy truck. Tanya yells out to Mama that I’m bothering the baby and then says don’t step on her shoes.

Mama leans in the door and says go throw the ball with that dog and I say it’s too hot. Mama says well do something and I ask what. She says you better think of something before I think of something for you.

And then Tanya pipes up and says she wants a snowball.

Before you know it, Mama reaches in her purse and pulls out some money and tells me to take Tanya down the street and get her a snowball. “Get one for yourself, too,” she says.

So out the door we go.

That sun’s beating down on us all the way down the street. Tanya’s about to step in an anthill so I push her to one side and she knocks up against somebody’s fence and turns around and says, “I’m telling,” and I say, “You want fire ants crawling all over your feet?” And she sticks out her tongue at me!

“I ain’t never taking you for a snowball again,” I say.

“Meanie,” she says, and sashays on down the sidewalk like she thinks she’s grown.

The lady at the snowball stand has sweat running down her face. Tanya’s standing there with her finger in her mouth trying to decide what flavor she wants. I can’t hardly stand up, it’s so hot.

“Just say bubblegum,” I say. “You always want bubblegum.”

“Now I want something different,” she says, and keeps on standing there.

“Maybe green,” she says.

“Mint?” the lady says, and mops the counter.

Tanya makes a face. “Pink,” she says.

“Strawberry or cherry?” the lady says.

Tanya’s finger goes back in her mouth and I roll my eyes.

“You’re holding up the line,” I say to Tanya.

Tanya looks around. “There ain’t no line.”

“I’m the line,” I say. “And I’m waiting.”

Tanya heaves a sigh. “Bubblegum,” she says. “I’ll have bubblegum.”

“What about you, son?” the lady says.

I’ve got my mind all made up. I open my mouth to say strawberry, and then—I shut it. All a sudden, I’m thinking I don’t have to buy a snowball. I can save that money. Mama won’t ever know.

“Nothing for me,” I say.

Tanya spins around. “Well, why are you fussing about me if you ain’t getting nothing yourself?”

“That lady’s waiting,” I say. “You’re taking up her time.”

I pay for Tanya and put the same amount in my pocket.

All the way home, I’m trying to make a plan. How many times do we have to get snowballs before I can buy another bag of food? What if Tanya tells Mama I didn’t get one? Wonder if anybody else wants somebody to take their little kid to get a snowball? I’m trying to do all the numbers in my head. They ain’t working out like I want. I’m thinking I need a piece a paper if I’m going to figure all this out.

When we get home, I forget all about the paper. Buddy takes a good, long look at Tanya and decides he better clean her up. He starts licking her face. He’s licking her hands. He’s licking her legs. He’s sniffing her sandal shoes and poking his nose at the leftover paper from the snowball. Tanya’s laughing like she’s having the time of her life and Buddy starts up barking.

“You crazy dog,” Tanya says, laughing so hard she’s about to fall over. “I ain’t a squirrel!”

Finally I tell Tanya to get inside and clean herself up because she’s the worst mess I’ve ever seen in my life.

I throw the ball for Buddy and he g

oes to find it. Four times in a row. It’s a record. Then he goes over to his bowl and slurps out some water. He looks up at me with his face all wet and drippy.

“You’re bad as Tanya,” I say, and he wags his tail.

“You ain’t got a lick of sense,” I say, and he wags his tail harder.

“You ain’t even worried about how I’m going to feed you, are you?”

Buddy says, “Rruff!” and I know that means “You’ll figure it out Li’l T. I know I can count on you.”

10

Saturday morning Daddy shakes me awake bright and early. “You forgot to do your job.”

“What job?”

“You’re supposed to cut the grass. You ain’t run the lawn mower in over a week.”

I can’t help it. I make a face.

“Just for that,” Daddy says, “you can cut Mrs. Washington’s grass, too. With her nephew gone she ain’t got nobody to do it—and you ain’t got nothing else to do.”

I look up at Daddy and he’s standing there with his arms crossed over his chest. I pull the pillow over my face. “Why do I have to do Mrs. Washington’s, too? Why can’t somebody else—”

“Just for that you can do it this week and next,” Daddy says. “You better quit while you ahead, boy, and get out of that bed.”

There ain’t nothing for it. I have to do it.

When the grass starts growing in the spring, it ain’t so bad. Everything’s all fresh and green, the air’s even a little cool, and you don’t have to mow but maybe once every two weeks. But by the time summer comes, the air feels like a wet rag laying across your face and the mosquitoes are biting all day. You have to do it at least once a week and even then there’s so much cut-off grass laying there you have to rake it up and spread it under the bushes. Granpa T keeps saying he’s going to get one of those mowers with a bag on the back but there ain’t never enough money for that, so I just keep on raking.

When I make it out to the shed, Buddy’s standing there waiting for me like he knew I was coming.

“What do you want, Buddy?” I say, and he says, “Rruff!”

I drag the mower out of the shed and gas it up. I yank on the cord and when it starts up, Buddy yelps and hops back into the shed.

“You stay right there,” I yell. “I ain’t going to be long.”

I whip that mower around the yard so fast Baby Terrell ain’t even finished with his bottle by the time I’m done.

Buddy comes creeping out of the shed when I start raking up the grass.

“This is a fool thing to do, ain’t it, Buddy?”

He’s poking his nose in my pile of grass.

“Why people can’t let their grass just grow, I don’t know.”

I rake that grass up under the bushes, sling the rake over my shoulder, and shove the lawn mower through the gate.

Buddy’s standing there on his three legs, panting in the heat and wondering what he’s supposed to do.

“You stay here, Buddy,” I say. “I’ll be back.”

He sits right down and he waits.

Mrs. Washington lives two streets up and around the corner. It ain’t that far to walk but it’s far to push the mower. I’m already hot by the time I get there and I just get hotter walking around and around in the sun. She ain’t got a single tree in her yard. Mama says she won’t let any grow there because she’s afraid they’ll fall over in a storm and crush her house.

I think old people get crazier every year.

When I’m done, I’m about to push through the gate when she opens the door and walks out on the porch.

“I’ve got a cold drink inside,” she says. “You want one?”

I know Buddy’s waiting, but I don’t ever turn down a cold drink. I roll the lawn mower around to the backyard so nobody will steal it and she opens the kitchen door and lets me into the cool.

Her house is tiny. Her kitchen is just about big enough for two people to stand in. She opens her refrigerator and I step into the hallway.

“What kind do you want?” she says behind the door.

“Have you got a Coke?”

“I do,” she says. “Here it is.” The door shuts and she stands up and hands me a cold drink. It ain’t a Coke. “That’s the last one,” she says.

I don’t know what to do. I pop open the top and take a sip. It’s good, but it ain’t a Coke.

“Sit down,” she says, and points to the front room sofa.

I sit down.

“I’ve got a letter,” she says, and pulls a letter out from under the lamp sitting on the table by the sofa. “From Iraq,” she says. “You want to read it?”

What am I supposed to say?

She hands it to me. “Open it,” she says. “Read it. Out loud.”

“Dear Aunt Mary,” it starts out. I look up at her. She’s looking at me through her big, thick glasses. All a sudden it dawns on me. She can’t hardly see.

She can’t see it ain’t a Coke. She can’t see to read her letter.

I put down the cold drink and start to read all the things her nephew has to say. How he misses this and how he misses that. How the other brothers are good and they’re a team. How he’s worried about her all alone. How he can’t wait to get home. How he’s got plans to fix up the kitchen. How he’s got to go now but he’ll write again soon.

I finish it up and look over at her and she’s smiling. “He’s a good boy,” she says, and stands up. She reaches in her purse and hands me a five-dollar bill. “You didn’t think you were mowing for free, did you?” She laughs. “You come back next week. You can read his next letter.”

When I get home, Buddy’s waiting for me at the gate. I push the lawn mower toward the shed and he’s sniffing at the wheels. I roll the lawn mower into its spot and I sit down by Buddy’s blanket. He limps over and lays down with his head in my lap. I run my hand across his head. I brush the bristly ends of his caterpillar eyebrow. I pull on his ears and I scratch up under his neck. He turns his head and looks up at me.

“Mrs. Washington’s nephew is doing all right,” I say. “He sounds happy enough.”

Buddy shifts his head a little.

“Maybe I’ll join the army,” I say. “But I don’t want to go to Iraq.”

I rub behind Buddy’s ears.

“Mrs. Washington’s a nice lady,” I say. “She gave me five dollars.”

I look over at Buddy’s food bag. All a sudden, I have an idea, and one more time, I’m making a plan.

11

Granpa T says I can use the mower. Mama says it’s all right with her so long as I don’t go too far. Daddy says it’s fine but I have to pay him some for the gas. Tanya says I can use her markers to make my signs.

The next day I sit down at the table and start making signs. Tanya wants to help, but she still makes some of her letters backwards so nobody can read anything she writes. Jamilla would have been a big help but there ain’t nothing I can do about that. So all by myself I make up a whole pile of signs that say I’ll mow a lawn for five dollars. I put our phone number on them. Then I start walking the streets looking for houses to leave them at.

Most of the people, I know. I always knock on the door and if nobody answers, I just leave it in the mailbox. Sometimes somebody comes to the door. At J-Boy’s house, his mama comes to the door in her nightgown. I give her the note and she looks at it and says, “Ain’t you J-Boy’s friend?” and I say, “Yes,” and she says do I know where he is and I say no. Then she shuts the door.

By the time I get home, two people have already called and all a sudden, I’m in business.

“What are you going to call your company?” Granpa T says.

“Li’l T’s Lawn Mowing Service,” I say.

Granpa T nods. “Got a ring to it,” he says.

The v

ery next day I take the lawn mower out and tell Buddy good-bye and head off down the street. I mow three different lawns. I’ve got three five-dollar bills sitting in my pocket and every single one of those people said for me to come back next week. I’m rolling my lawn mower back to the house and I’m thinking maybe somebody else has called while I was gone when I look up and I see J-Boy walking up the sidewalk. We ain’t talked since school let out.

“S’up?” he says. He don’t smile or nothing.

“Not much,” I say.

“So are you mowing those lawns?” he says.

I nod. The sweat’s rolling into my eyes and I wipe it out.

“That’s hard work for slow money,” he says.

“Money’s money,” I say, and look down at the lawn mower. It’s got new grass all stuck on the sides. The rubber gripping part under my hands is starting to work loose.

J-Boy takes one finger and rubs it across under his nose. I can’t help it. I see he’s starting a mustache.

“So where is that dog?” he says.

“He’s in the back. Do you want to see him?”

We stand there another second. J-Boy’s looking off down the street. He hikes up his pants a little.

“You don’t have to if you don’t want to,” I say.

“I’ll come.” He follows me through the gate while I’m pushing the lawn mower to the back.

We turn the corner around the house and there’s Buddy, standing in the door of the shed, his tail whacking back and forth.

“Hey, Buddy,” I say, and drop on my knees in front of him. “You miss me? You miss me, boy?” I’m rubbing his head. He’s licking my face. His whole body’s shaking, he’s so glad to see me. “This is J-Boy,” I say to Buddy. “From down the street.”

J-Boy’s hanging back. His hands are shoved into his pockets.

Buddy’s looking up at him and grinning.

“He likes you,” I tell J-Boy. “You can pet him if you want to.”

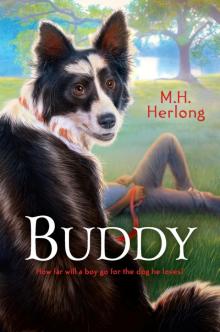

Buddy

Buddy The Great Wide Sea

The Great Wide Sea